In the warm coastal regions of Asia, Australia, North and South America and parts of Africa, hermit crabs have turned their backs on the sea and live on land. However, of the more than 1,100 species of hermit crabs distributed among 120 genera, only a scant 20 species, classified into two genera, have made this move. they are the land hermit crabs (Coenobita) and the closely related palm thief (Birgus latro), the largest land-dwelling invertebrate in the world. All other hermit crabs live in the sea. There are good reasons for this: first, hermit crab larvae can only develop in the sea, and second, hermit crabs, like all crabs, breathe through gills. The latter problem has been trickily solved by land hermit crabs, as will be read later. The other problem persists. The land hermit crabs still have to return to the sea to release their larvae. That is why these animals are always found relatively close to the coast, because such a small animal cannot crawl further than a few kilometers, even if this is only necessary once a year.

Most species turn up in the pet trade from time to time, often misidentified. In principle, this is not a problem, because all land hermit crabs are excellent terrarium animals, but the different species have quite different requirements for housing and care. Above all, the question of whether or not salt water needs to be provided is quite important. As mentioned at the beginning, land hermit crabs also breathe via gills. For this purpose, they dip specially shaped, brush-like legs into water and moisten the gill cavity located inside the body; because only if they are sufficiently moistened, gills can function. For some species, freshwater is sufficient to keep the gills functioning, but others need seawater to do so.

Because of the gill breathing, land hermit crabs are also mainly nocturnal, because then the humidity is higher. In terms of their activity times, they can be compared quite well with our Central European land snails, which can also be found during the day only in rainy weather. Land hermit crabs spend the day buried in moist soil. Therefore a minimum of 10 cm, better 15 cm high substrate in the terrarium is elementary important for a successful care of land hermit crabs. Land hermit crabs also need this for molting. Like all crustaceans, land hermit crabs need to molt in order to grow, as the crustacean shell cannot grow. Juveniles molt several times, adults usually only molt once a year. If the substrate is not deep enough and sufficiently moist (not wet!), molting problems will occur, which are usually fatal for the crayfish. The depth of the substrate is critical because only in complete darkness is the hormone needed for molting produced in sufficient quantity. Since the land hermit crabs need a larger snail shell after molting, one must always provide sufficient empty snail shells of suitable size in the terrarium.

Land hermit crabs cannot tolerate cold. Therefore, the terrarium temperature must always be above 18°C, preferably in the range of 20-26°C. Land hermit crabs are omnivores, so their diet does not cause any problems. A large handful of autumn leaves forms the food base in the terrarium and should always be available. Add to this fruit, vegetables, salads, fish food flakes, pellets, canned cat and dog food, small dead fish, etc. One should always give only so much of these kinds of food, as is eaten up over night completely. The exact amount of food must be determined by yourself, since the animals develop different appetites at different times of the year and depending on the moulting interval. Daily spray the terrarium with lukewarm water, preferably in the morning and evening. For the furnishing you can use gnarled roots, branches and stones, but be careful: the little rascals develop amazing powers! Stones must also rest on the terrarium floor, so that they cannot be burrowed under and possibly become a death trap. Every day, place a shallow bowl of fresh water and – for species that need it – a bowl of seawater in the terrarium.

Basically, land hermit crabs are social animals that communicate with each other even by means of very quiet chirping sounds. Therefore you should keep them in a group, 5-6 animals are good, 10-15 are better. The sexes can only be distinguished when the animals change house; females can then be recognized by the additional legs on the abdomen, to which they attach the eggs and carry them around until hatching maturity. They then begin the migration to the sea – a perilous time when a great many females perish in the wild. When they reach their destination, many more females drown, because land hermit crabs can no longer live underwater. But each female that makes it releases hundreds of larvae that, after a few weeks in the plankton of the oceans, become miniature hermit crabs and go ashore. Even though, as with almost all wild animals, over 99% of the young born die early, in the case of land hermit crabs there are so many that in fact the number of empty snail shells available on the ocean shore is the limiting factor in how many land hermit crabs can transition to land life.

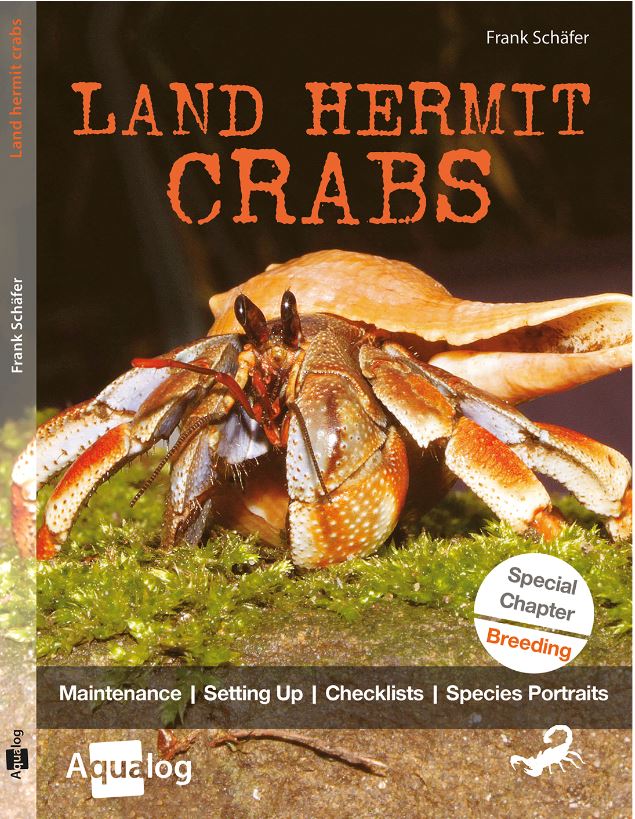

Land hermit crabs are very beautiful, highly interesting terrarium animals. If you are seriously interested in their care and breeding, you cannot avoid the book “Land hermit crabs“, because it is the only book in the world in which all known species are considered and in which numerous tricks and tips that save from disappointment are presented in a practical and easy to understand way.

Frank Schäfer

Book Tip: