When did humans begin to keep reptiles? Of course we don’t know exactly, but crocodiles and snakes played a major role in the religion of Ancient Egypt. Crocodiles had temples of their own and so did snakes. It is probable that every type of animal maintenance was originally for religious reasons. The keeping of animals in the Stone Age, during the so-called Neolithic revolution, was undoubtedly originally influenced by religion. Otherwise why were cattle domesticated, but not bison? To the present day there are cult practices involving cattle, based on ancient myths, for example bull fighting in southern Europe and holy cows in India. But reptiles certainly weren’t domesticated back in the days of the ancient civilizations, and their culture wasn’t a matter for the common people, and certainly not for pleasure.

Nile Crocodiles were worshipped in temples more than 4,000 years ago.

For many thousands of years swamp and aquatic turtles have been revered as symbols of longevity, wisdom, and good luck in Asia; they are kept in artificial ponds, but here too the religious aspect is pre-eminent.

In the Mediterranean area (and undoubtedly elsewhere as well) tortoises were regarded as live food reserves; there is considerable evidence that numerous populations that exist today are descended from introductions by ancient peoples, above all the Romans. In addition the majority of European occurrences of the European Chameleon (Chamaeleo chamaeleon) are thought to originate from the introduction by humans of specimens from North Africa or western Asia (where, despite its popular name, the species has its main distribution). But a date cannot be put on this.

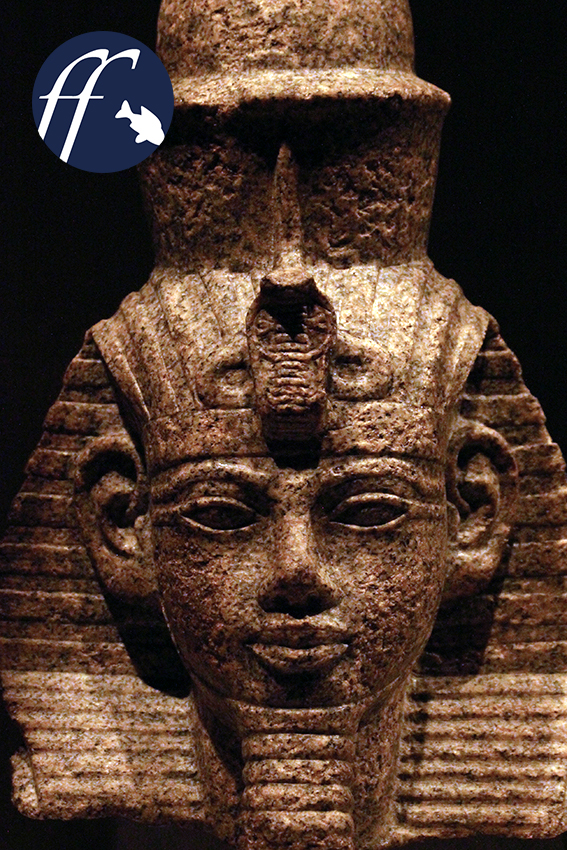

Meanwhile for thousands of years it was only snakes that were kept and worshipped in temples; sometimes these were venomous species, but more frequently harmless ones. The tradition of snake charming is very ancient and probably dates back to the cobra cult in Ancient Egypt. The indigenous Egyptian Cobra (Naja haje), also known as the Asp, was a component of the crowns of the Pharaohs, where it represented both a “third eye” and a defense against enemies. There is a nice list of snake cults in Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serpent_(symbolism)

Sculpture of the Pharaoh Amenophis III (ca. 1360 BC) with Asp.

The Asp (Naja haje) is used by snake charmers in Egypt to the present day.

But leaving aside cults and religions, the keeping of reptiles first began at the end of the Middle Ages and the associated period of enlightenment. It was, however, and still is to the present day, invariably plagued with superstition and lack of understanding on the part of those who didn’t keep reptiles. For this reason it has always been very special people who dedicate themselves to the terrarium hobby.

As far as I know, the first real terrarium keeper (i.e. someone who keeps reptiles of their own free will without any useful purpose in mind) was in all probability Louis XIV of France, famous as the Sun King, who embodied absolutism as a form of government (“I am the state”). So he can certainly be described as a very special person … Louis XIV maintained one of the first modern menageries. A menagerie is a collection of live animals where the latter are kept solely for the edification of their keeper, without the scientific and educational requirements of a zoological garden.

- Europäisches Chamäleon (Zypern)

- Europäisches Chamäleon (Zypern)

- Europäisches Chamäleon

- Europäisches Chamäleon

- Europäisches Chamäleon

- Europäisches Chamäleon

- Europäisches Chamäleon (Türkei)

Photos 1-2: European Chameleon (Cyprus) / Photos 3-6: European Chameleon / Photo 7: European Chameleon (Turkey)

The Louvre in Paris is one of the most important museums in the world for works of art. Its collections also contain a number of splendid drawings made by the Dutch artist Pieter Boel (1622 – 1674) in the menagerie of Louis XIV. In addition to the usual species that might be expected in such a collection, i.e. hoofed animals, monkeys, pachyderms, small predators, big cats, and a multitude of birds, there were also the European Chameleon and the Green Lizard (Lacerta viridis)! I find that very very noteworthy, as generally speaking the people of the 17th century didn’t regard such reptiles as “attractive”. The drawings by Boels are so true-to-life as to evidence the excellent state of health of the animals maintained in the menagerie. This would have been anything but guaranteed, as the term “hygiene” was completely foreign to the people of that period. But the animals were obviously doing well, their body posture shows that they were alert and interested in their surroundings. There was certainly no cruelty to animals involved in the maintenance of the menagerie of Louis XIV.

- Smaragdeidechse, Männchen

- Smaragdeidechse, Weibchen

- Smaragdeidechse, Männchen

- Smaragdeidechse, Männchen

- Smaragdeidechse, Männchen

- Smaragdeidechse, Männchen

Photo 2 shows a female Green Lizard, all other indivduals are males.

Nevertheless the chameleon(s ?) probably didn’t live all that long there, as an adult chameleon has a natural life expectancy of only around two years. In particular overwintering is most unlikely to have been successful given the state of knowledge back then, but who knows? No information on the subject has been handed down, and it is quite conceivable that these creatures spent the cold part of the year in the orangery, where they should generally have been able to survive the winter.

Be that as it may, the Sun King was probably the first terrarium keeper in the modern sense!

Frank Schäfer

A wonderful de luxe volume of the drawings of Pieter Boel has been published by Paola Gallerani at Officina Libraria. ISBN: 978-88-89854-74-7. The home page of the publisher can be found at http://www.officinalibraria.com/home.php

Further literature on chameleons can be found at www.animalbook.de

Anzeige