The mudskippers represent the culmination of evolution as regards living on land. Mudskippers belong to the goby family, the most successful of all the fish families in existence today. With 1,843 species currently known (and that is at most half of the species that exist!), the gobies are one of the most species-rich of all fish families. Within the goby family (Gobiidae), the mudskippers belong to the subfamily Oxudercinae.

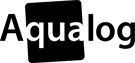

Mudskipper (Periophthalmodon septemradiatus)

Mudskippers invented the aquarium long before humans. For unlike all the other land-going fishes previously mentioned, mudskippers don’t have an auxiliary respiratory organ with which to breathe atmospheric air. They are completely dependent on their gills for breathing. So how do they manage that when they go ashore? Well, as already stated, by using an aquarium. Mudskippers are able to close their gill-covers so firmly as to create a water-tight container. Which they fill with water. And just as we aquarists pump air into the aquarium via an airstone, the mudskippers keep taking in fresh air and mixing it with the water in their “gill-cavity aquarium”, thus enriching it with oxygen.

Mudskippers – there are two genera, Periophthalmus and Periophthalmodon, which can be distinguished by their dentition – orientate themselves primarily using their vision. This too is an adaptation to life on land. As we have seen in the two previous parts of this article, the sense of sight is of relatively little importance under water. “Normal” fishes, when blinded, manage very well without eyes, as they possess numerous other sensory organs that permit them to orientate themselves perfectly well in water. But these senses don’t work very well, if at all, on land. In particular the ampullae of Lorenzini (electro-receptors) and the lateral-line system, able to detect the slightest changes in pressure under water, are useless in air. Only the senses of sight and smell function well, but then only if the surfaces of the sensory organs are kept moist. In the case of eyes, normal terrestrial vertebrates have invented the eyelid for this purpose. The eye is kept moist by continuous blinking and so remains functional. Only the snakes have taken a different route. In their case the eyes are covered with a transparent membrane, beneath which there is adequate moisture. The membrane covering the snake’s eye is shed every time it molts; for this reason a snake is practically blind shortly before molting, as can be seen from a milky-white clouding of the eye.

Note the pits beneath the eyes…

Fishes don’t have eyelids. So how have the mudskippers solved this problem? Answer: with a second aquarium! The true mudskippers, i.e. those that genuinely venture onto land, have an indentation beneath each eye, and this is kept full of water. In order to moisten their eyes, which are set high on top of the head, mudskippers fold them down into these indentations.

In mudskippers the mucus membranes responsible for the sense of smell are kept moist in exactly the same way as in humans: they are situated in cavities inside the body, where they won’t dry out as easily. Moistening of the organs of smell takes place entirely during the baths taken regularly by mudskippers: in the interests of maximum mobility, the surface of their bodies is covered exclusively with very small scales, and these don’t provide very good protection against drying out. So depending on the weather, mudskippers have to take frequent short baths.

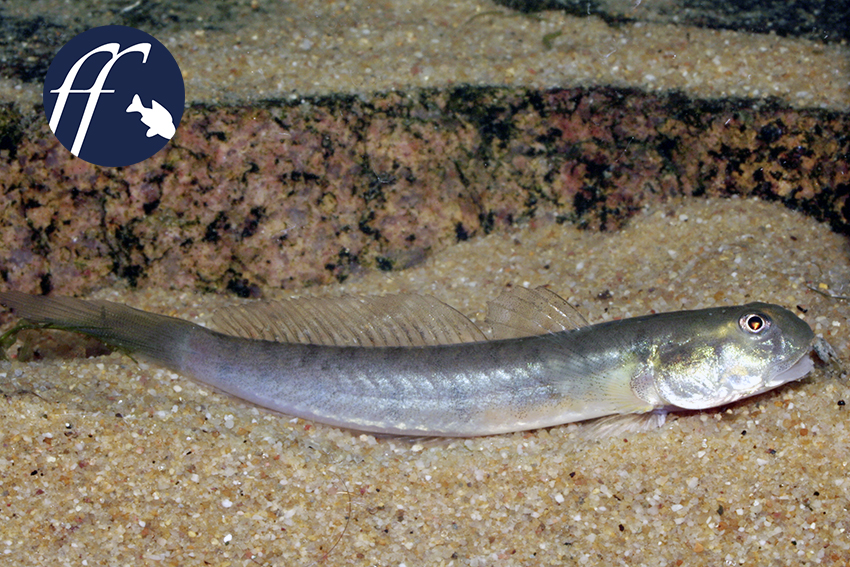

Apocryptes bato

The subfamily Oxudercinae provides a wonderful opportunity for studying the stages of adaptation to life on land. The most primitive relative of the mudskippers, which still lives like normal gobies, is Apocryptes bato; the genus Apocryptes contains just this one species. These attractive gobies with their highly expressive eyes live in the region of river mouths. For this reason they have achieved a significant degree of adaptation to variable salinity of the water. Mudskippers need to be adaptable in this respect, as they live in tidal zones. When the tide comes in mudskippers live in water, but on land at low tide. Because in the event of a violent local shower of rain, such as is commonplace everywhere in the tropics, it may happen that the fishes suddenly have to deal with completely fresh water, and shortly afterwards, when the tide comes in, with full-strength sea water again.

Pseudapocryptes elongatus

Like these two Periophthalmodon septemradiatus, Pseudapocryptes also sometimes take a look around above the water.

Pseudapocryptes are close relatives of Apocryptes. These droll gobies – there are two species – are adapted to shallow water, but never leave it voluntarily. In the aquarium they are best maintained in water 8-15 cm deep. It can then very readily be seen how these fishes sometimes adopt an S- or C-shaped posture, resting on their caudal fins, and at the same time raise their eyes above the water’s surface, so that they can observe their surroundings, including the land. This behavior probably serves as a defense against enemies, as from Pseudapocryptes‘ point of view the majority of predators attack from above.

Scartelaos hispidus

Boleophthalmus boddarti

Scartelaos (4 species) and Boleophthalmus (6 species) represent a step further in the direction of land. Their method of locomotion very closely resembles that of the true mudskippers: their pectoral fins are attached to (albeit very short) arm-like stalks and the lower part of the caudal fin has robust rays that are used as a counter-balance, much like the tail feathers of a woodpecker. When necessary, these fishes can use these fins to accelerate forward at great speed. But neither Scartelaos nor Bolephthalmus ever leaves the water completely, preferring to have at least a thin film of water beneath their bellies. The members of both genera feed predominantly on very small particles that they collect from the tide line.

Mudskipper males (this is Periophthalmus barbarus) use their splendid dorsal fins for communication.

The special structure of the caudal fin is readily visible in this Periophthalmodon septemradiatus.

By contrast, the true mudskippers, i.e. Periophthalmus (19 species) and Periophthalmodon (3 species), are genuinely terrestrial, and don’t really spend much time in water at all, except for flight. Their prey – mudskippers are opportunistic omnivores, whose preferred food is small organisms – is captured on land, and their social life also takes place there. The mudskipper species differ from one another externally mainly through the strikingly-colored dorsal fins of the males. These are used like colorful flags to signal readiness for battle, courtship, and so forth. These fishes prop themselves up on stout “arms” and use their pectoral fins like feet; there is no question but that mudskippers are better adapted than any other vertebrates to the tidal zone of the mangrove swamps. Who knows, maybe in the course of a few million years they will give rise to a second lineage of terrestrial vertebrates, a new taxonomic class, comparable to the classes of the mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fishes alive today…

That is undoubtedly the answer to the question posed right at the start, “Why did fishes venture onto land?” – simply for the sake of change. The purpose of all life consists on the one hand of survival, and on the other of evolving further. This works only through the perpetual cycle of birth and death, as without an end there can be no new beginning. And so the move onto land by fishes, to which we ultimately owe our existence, was no more than the implementation of a principle that all life on Earth must follow.

Frank Schäfer

Anzeige